The Dome Chronicles: Charlie Harris’ Mill

By Garry Leeson

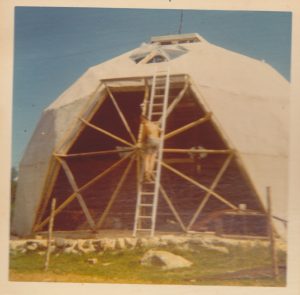

In 1972, a boxcar from Toronto containing a menagerie of farm animals and an eager young couple pulled into the station platform in Kingston, Nova Scotia. They were bound for a deserted hundred-acre farm on the South Mountain, determined to preserve the foundations of farmsteads past while constructing a geodesic dome. They were pioneers of the future, armed with respect for tradition and an irrepressible sense of humour. They didn’t call themselves farmers. They were back-to-the-landers. Farming was industry and their calling was sustainability. Over the next forty years, through flood and fire, triumph and catastrophe, they persevered, unwittingly sowing the seeds for the modern small-farm movement.

In the summer of 1973 I needed some lumber to finish our dome, so I picked up my cantankerous old blue Homelite chain saw and headed to the woods. Felling the trees and yarding them out with my old mare, Lady, was a hard slog but that was only part of the job.

Portable mills like Wood Miser were not available in those days; I was going to have to truck the logs to Charlie Harris’ sawmill located above the Berwick Power Dam in Morristown. All the little privately owned mills, like Charlie’s, were slap dash affairs thrown together with anything the owners/ self-appointed mill wrights found lying around. The main source of power for these installations was usually an old car or truck rendered stationary, then cut more or less in half so that the driveshaft was exposed and accessible and then connected, via a series of U joints and shafts, to the pulley that drove the saw. The big circular saw and its mandrel were factory made but the rest of the gear was fashioned out of yet more scrounged things as diverse as bicycle parts or innards of retired wringer washing machines.

The Harris mill wasn’t a pretty sight and when it was fired up, howling and belching black smoke, it was something best observed from a distance.

Unfortunately, staying clear of the mill wasn’t an option if you planned on using Charlie Harris’s services. He was chronically short of help so anybody getting their logs sawn was required, personally, to unload and roll his own logs up to the business end of the contraption to where the circular saw, a screaming, whirling, four-foot-in-diameter disk of death was located.

I was nervous as I performed my end of the bargain rolling the logs off my truck and up to the saw with that god-awful power take-off shaft spinning and vibrating away a few feet below the ramp. Everything went well until, on my final trip, I was unloading the last few logs. They weren’t huge logs, but there were some that I needed a peevee (a hook affair on the end of a long shovel handle) to roll along, but for the most part, they were small enough that I could lift one end to readjust its position if necessary.

I guess I had grown too confident and excited about coming to the end of the job because as I was scooting one of the smaller logs up the ramp, I lost control of it and it rolled over the edge and fell into the pit below.

“Not a problem,†I thought to myself. “I can easily get this baby back up on the ramp one end at a time.†It wasn’t very far to the ground where the log lay – maybe five feet or so – so I went to the side of the ramp, stepped off, and landed flat footed beside it. At the time, I was sporting an outfit that I liked to think made me look like one of the locals; bare-chested with a loose fitting pair of heavy denim bib overalls. It had been a damp morning so I was still wearing a pair of standard issue farm rubber boots.

There is a gap in my memory covering what happened next. I remember a sudden shock and something akin to an explosion of bright white and yellow light then nothing. When I came to, I was flat on my back with a huge dense cloud of small blue particles floating over me. I could hear the sawmill grinding to a stop and some frantic shouting nearby. I gave myself a shake and tried to get to my feet but one leg did not seem to want to respond immediately. Shortly, Charlie Harris and my brother-in-law, Ed Kuhn, helped me to my feet. It was kind of embarrassing for me because, as I glanced down and took stock of myself, I realized that, except for one rubber boot and a chunk of my overall brace hanging limply over my shoulder, I was buck naked!

By then the motor had stopped and the mill had rolled to a complete stop. I could see what was left of my overalls lodged in the universal joint of the main drive shaft. Somehow while manoeuvering the fallen log, I had stepped too close to the shaft and a loose flapping thread from my pant leg had been drawn into the whirling shaft tearing me off my feet. Since my knee joint was throbbing painfully and had ballooned to three or four times its normal size, I assumed that at some point it must have made abrupt contact with the drive shaft. The cloud of blue particles that hung in the air was all that was left of my overalls. They had been ripped, torn, shredded, and pulverized into a fine powder by the powerful whirling shaft – so powerful that if my clothing and I hadn’t parted company the rest of me would have suffered a similar fate. I got to my feet and with my hands covering my essentials, rejoicing that they were still there, staggered towards my truck.

I remember saying “I think I better go home now, Charlieâ€.