EDITOR’S UPDATE

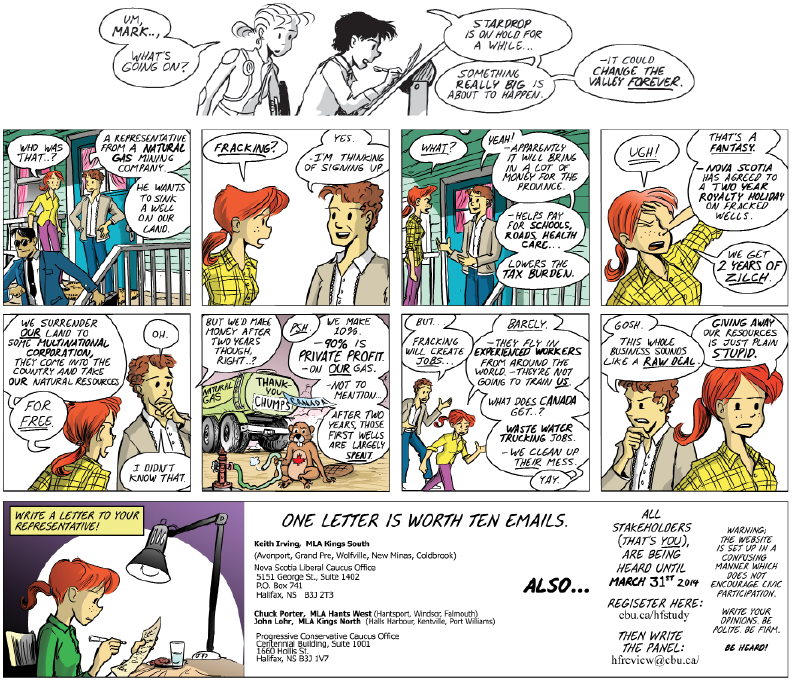

“I now have very little appetite to participate in such a discussion in the Grapevine, especially given the cartoon that was presented in the last issue. ‘Fracking’ is clearly not an issue that your newspaper is interested in dispassionately discussing (note that the cartoon in the last issue was not labelled as an editorial, which it clearly was, and so you failed your readership on that one).“  Of all the feedback from the February 6th issue, the statement above from an Acadia professor spoke to us the loudest. Our decision to run an anti-fracking cartoon strip from Mark Oakley was, admittedly, a little out of left field and we also agree that we failed to present a larger scope to the fracking debate. Last issue we distanced ourselves from the topic as we worked through some important internal discussions. What is the purpose of The Grapevine and what will it look like moving forward?  As an independent paper, we have an incredible responsibility and opportunity. The provincial deadline for public input on fracking ends on March 31st, so we felt like an entire issue dedicated to a more balanced look at this contentious debate was warranted. If we’re able to stimulate more discussions around the water cooler, raise community awareness, or encourage more written contributions to this provincial fracking review, then The Grapevine is doing exactly what we are meant to be doing. Well, that and reminding you about all the amazing arts and culture that continues to surround us here in the Valley! Please enjoy our first themed issue, oh, and remember: the opinions found within these pages do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Grapevine staff, our advertisers, or our other contributors.

Jeremy Novak and Jocelyn Hatt

![]()

Nova Scotia: Between 2007 and 2009, Denver-based Triangle Petroleum drills three hydraulic fracturing (“frackingâ€) wells, in Noel and Kennetcook, Hants County. After the company pulls out, Windsor town council agrees to work with Atlantic Industrial Services (AIS) to treat fracking wastewater. In 2011, the water is found to have naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORMs), and treatment is stopped. A year later, a ban is placed on receiving fracking wastewater from other provinces. Ponds in Debert and Kennetcook continue to hold 5 million and 20 million litres of wastewater, respectively. In January of 2014, Environment Minister Randy Delorey announces that AIS has developed a way to treat fracking water to the point where it poses “minimal risk†to people and the environment. In 2012, the Dexter government imposes a two-year moratorium on fracking. It expires mid-2014.

Ukraine: With an estimated 1.2 trillion cubic meters of recoverable shale gas, mostly in the western part of the country, Ukraine has the third-largest such reserves in Europe. In 2013, Ukraine signs a $10 billion deal with Chevron and an equally lucrative one with Royal Dutch Shell. Then-president Viktor Yanukovich tells investors that the two deals could make Ukraine not only independent of Russia for its energy, but a net exporter of gas by 2020. Commenting on the two deals, The Financial Times reports that they “could increase tensions with Russia.â€

Bulgaria: In 2012, Bulgaria becomes the second European country (after France) to ban fracking. The ban compels the state to revoke a major shale-gas permit for Chevron. Right-wing National Council member Ivan Sotirov writes in Bulgaria’s Trud newspaper that Russia, increasingly threatened by European countries’ increasing energy independence via fracking, was behind massive anti-fracking street protests.

United Kingdom: In December 2013, the Cameron government announces plans to “step up the search†for shale gas. They offer energy companies a chance to drill across 37,000 square miles—in every county in England except for Cornwall. A government report says that the wells could fulfill up to 20% of annual gas demand and create 32,000 jobs.

Texas: In 1997, Mitchell Energy has a breakthrough in extracting natural gas from the Barnett Shale, switching from gel frac to “slickwater†frac. By 2000, “fracking†and horizontal drilling, in combination, have made these new extraction methods profitable. There are now 12,000 wells on the Barnett Shale.

Pennsylvania: In 2012, Governor Tom Corbett introduces a law that limits municipalities’ say over fracking in the Marcellus Shale and elsewhere in the state. In December 2013, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court votes 4-2 to strike down portions of the law, saying they violate the municipalities’ constitutional right to planning with their residents’ welfare and quality of life in mind. Similar legal challenges are underway in Colorado and Ohio.

Ohio: In February 2014, Governor John Kasich reverses his position on fracking in Ohio state parks after it is revealed that his top advisers knew of a Department of Natural Resources plan to target anti-fracking “eco-left pressure groups†such as the Sierra Club, whom the DNR called “skilled propagandists.†Ohio has an estimated $100 billion worth of natural gas; however, since major fracking activity began in 2011, the state has suffered more than a dozen earthquakes in non-seismically active areas, and two injection wells have been closed as a result.

Los Angeles: In February 2014, L.A. City Council votes unanimously to start drafting rules that would place a moratorium on fracking and acidization until, as Councilman Paul Kortez puts it, “these radical methods of oil and gas extraction are at least covered by the Safe Drinking Water Act.â€

Quebec: In 2013, the Marois government puts a five-year moratorium on shale-gas exploration in the St. Lawrence Valley, with potential fines of $6 million. However, exploration and fracking are still permitted on the Gaspe Peninsula and Anticosti Island––a sparsely populated hunters’ haven where up to 80% of the land has been opened up to drilling. Opposition Quebec Solidaire Party member Amir Khadir explains the discrepancy by saying, “Deer don’t vote.â€

British Columbia: From 2000 forward, over 11,000 wells are drilled, including 180 in the Cordova Embayment in northeastern B.C. The Dene Tha’ First Nation is suing the provincial government to get an “independent body to hear [their] concerns†and compel the government and industry to provide “meaningful consultation and scientific reasoning†regarding the potential adverse effects of fracking.

Australia: In January 2014, a U.S. study estimates that Australia has 437 trillion cubic feet of recoverable shale-gas reserves, 10 times the existing known natural gas reserves. This puts Australia seventh in the world on the shale-gas rankings. Market analysts predict that Australia will be “the next big thing†in fracking, not least because many of the reserves are in sparsely populated areas where protests are unlikely to be a major concern.

Sources: The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, the Economist, The Financial Times, CBS.com, the Globe and Mail, the Phoenix Reporter and Item, Reuters, UPI, J. Daniel Arthur, the Energy Information Administration (EIA), American’s Natural Gas Alliance, Bloomberg News, The New York Times, Canadian Geographic, the Christian Science Monitor, The Daily Beast, Accuracy in Media, The Columbus Dispatch, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the American Enterprise Institute, AAPG Explorer, National Public Radio, CTV News, Hants Journal, Halifax Media Co-op. By Pamela Swanigan

FRACKING AND FARMING ARE INCOMPATIBLE

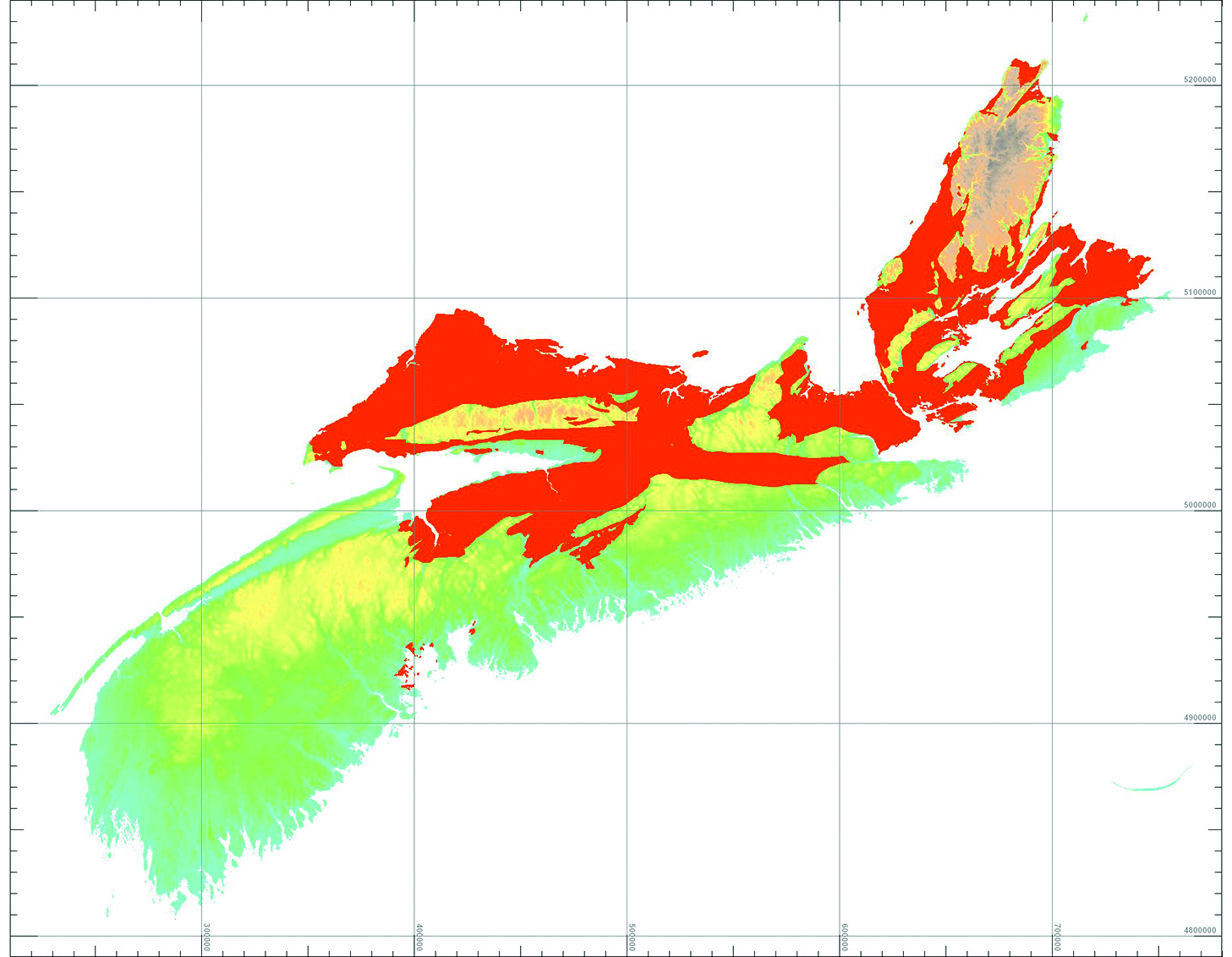

(Visual Maps for Fracking Review submitted with this article.)

On behalf of No Farms No Food,

Marilyn Cameron, DVM

Hawthorn Hill Farm, Grafton

Six counties in Nova Scotia hold 60% of arable lands for growing food: Cumberland County (14.8 %); Hants County (12%); Colchester County (11.6%); Pictou County (9.2%); Kings County (6%); and Halifax County (5.3%). According to the most current NS Department of Energy map of onshore petroleum-lease agreements, the areas where the majority of petroleum development (including shale-gas methane) is expected to occur are in the same locations as most of our province’s best agricultural land.

This is very disturbing news. Nova Scotians would have a lot of trouble reconciling the investment of countless millions of dollars to support programs for farmers, to pay taxes on farmland, to provide numerous subsidies, to promote buy local initiatives, etc., while our government allowed fracking companies to destroy agricultural land.

In 2010, the Agricultural Land Review Committee carried out extensive research and public consultation to examine how much land suitable for growing food and fibre is needed to ensure food security for Nova Scotians. They determined that Nova Scotia just might have enough arable land to support our current population of 900,000; however, more than two-thirds of it is covered in forest. Today, each person in the province utilizes 0.2 hectares of land to grow her or his food. It has been calculated that each person requires an estimated 1.4 hectares of farmland to provide a complete diet (as per Canada’s Food Guide) of fruits, vegetables, meat, dairy, eggs and fibre. Thus, we need a minimum addition of 853,000 hectares of cleared land to be self-sufficient. The cost to clear one hectare of forest lands for agriculture is $4,000-$5,000.

Our agricultural industry puts $462 million into our economy each year (as of 2008) and directly provides 6,400 jobs (80% full-time) and another 5,400 food-processing jobs. These jobs have the potential to last forever if the land base is preserved, whereas gas exploration creates far fewer jobs that are largely temporary—as is typical for boom and bust industries.

The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) established a set of guidelines in 2006 that pertain to healthy soils. Fertile soil contains a complex mixture of minerals, organic matter, water and air along with a host of organisms like bacteria, fungi, protozoa, invertebrates, and other tiny animals and plants, and can have millions of electrochemical reactions within a single handful. Toxic chemicals introduced into soils with a healthy functioning ecosystem not only damage the microbes and invertebrates that make soil fertile, but also create exposure risks to humans and wildlife through groundwater contamination, bioaccumulation and/or bio-magnification into foodstuffs, soil erosion through runoff or wind action and volatile reactions of soil chemicals being released into the air.

Impacts from fracking on rural communities, in addition to contaminated water and foodstuffs, are considerable. They include noise and light pollution, nitrogen oxide emissions, earth tremors and accidental spills, leaks and emissions of fracking chemicals, methane gases and hydrogen sulfide gases.Why should rural residents be denied quiet enjoyment of their properties and protection from harm as is their right under the Nova Scotia Municipal Government Act if industrial fracking activities are permitted in close proximity to their communities and farms?

A multitude of reports speak of shale-gas exploration and drilling as being a formidable land disturber. Patrick Drohan, an agricultural researcher at Penn State University, concluded that shale-gas development will dramatically change the quality of both private agricultural land and public forests as development of new roads to support drilling fragments farmland and forest ecosystems and diminishes water reserves needed for agricultural communities. Livestock near fracked wells also tends to do poorly and can experience respiratory and reproductive tract illness and neurological disorders. Dairy cattle can have decreased milk production.

We do not need to experience firsthand the negative impacts caused by this industry to farms in order to learn the bitter lessons that so many others have in their rural communities. What the shale extraction industry has done in other communities, it will undoubtedly do to us here in Nova Scotia.

Farming can be very rewarding but is made so much more difficult when the farmland is encroached upon by urban sprawl, commercial development or, much worse, by industrial activity.

If the Review of Hydraulic Fracturing truly evaluates the full risks and benefits, as we expect it to, then we believe that the Review cannot fairly conclude that fracking will not harm our resources, like farmland and water in any way.

References upon request.

Marilyn Cameron is a small animal veterinarian who graduated from the Atlantic Veterinary College in 1997. In 2010, Marilyn, along with her husband and their daughter, bought a 46 acre farm in Grafton – called Hawthorn Hill Farm. They are registered with the Nova Scotia Federation of Agriculture. Their largest crop is pears and garlic and they have a multitude of other small fruit crops such as strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, haskaps, cheeries and blueberries, plus vegetables in our fields. All of their crops are no spray except the pear orchard. The rest of their field acrage is used for hay production. The family also raise a small flock of shetland sheep for wool and have heritage hens for egg production.

BALANCE

Nathan W. Rand     Â

I have always been proud of Nova Scotia’s forward-thinking environmental policies and its residents’ care for the province they love. From the uranium moratorium to opposing quarries to leading the country in household-waste separation, collection and composting, it is clear that these decisions have been made with the educated and sober reasoning that our future generations deserve. However, I am wary of the current fracking moratorium. Granted, in its current form it is in effect to buy time for proper research, review, and (I assume) the creation of legislation governing the processes, procedures and safeguards (perhaps naïve to ignore pushing a divisive issue away from election cycles, so call me optimistic). Calm, well-informed, and balanced decisions when it comes to the environment anywhere and particularly the sea-bound coasts I call home are imperative. My sincere hope is the public weighs the economic and environmental benefits evenly with the risks.

Water is the heart of the opposition to fracking, and we need to face the fact that water is a visceral issue, tempering our quick reactions accordingly. Yes, we all need it, our crops need it, our livestock needs it, and in some cases industry too. The average frack can use water volumes ranging from 2 to 10 swimming pools like Acadia’s. That is not much if you are looking toward Blomidon at full tide, but a terrifying amount flowing through your basement carrying your freezer away. A portion of this frack water can be recycled, a portion remains down-hole, and the remainder needs remediation and disposal—a problem solvable with time, research and proper planning. In my opinion the wildcard risk is the potential for a frack-related increase in seismic activity. An earthquake like San Francisco’s in 1906 is far-fetched for Nova Scotia, but the small quake felt in the mid-1980s turned a few coastal wells I know of brackish. Living on a maritime peninsula with excellent well water we have all heard these stories. In every anecdotal case that I have heard, the affected parties found alternative sources on their own. If responsibility is built into the development of these natural-gas resources from the beginning, it should be possible to plan for the inevitable problems and accidents that will occur. All development carries risk, so there must be industry-funded legacy trusts set up for remediation and compensation when things go wrong. With superior monitoring like frequent water testing in and around fracking areas, contingencies developed for any affected parties could be initiated quickly. They would be able to rest assured that they will be taken care of and not have to fend for themselves. All funded by producers, administered and reported independently.

NS Power generates 59% of its electricity from coal-fired plants. Natural-gas power plants release fewer emissions while providing on-demand power. If royalties and rebates work like those in Alberta, NS Power could buy into one of the producers and receive a lower rate. We all want a lower power bill, but the real boon would be industry. Cheaper generation costs mean power could be offered to manufacturing industries at more competitive rates. With ready access to rail, shipyards, and the northernmost ice-free deep-water port on the continent, Nova Scotia could capitalize on its own riches, geography and workforce again. Encouraging growth of value-added businesses by leveraging resources already present in the province will grow the availability of lasting and lucrative jobs in the province. Information from a quick Internet search (insert grain of salt) shows that the gas in the Horton Bluff Shale could amount to three times that in EnCana’s Deep Panuke offshore project. Opening up the province to responsible, controlled, and monitored fracking development could provide work for the underemployed residents while bringing both the skilled and unskilled back home to work toward creating a future in the province for those of us who want our children to grow up in the same beautiful and enchanting places we did. Imagine being able to put royalties earned from these resources back into provincial infrastructure, and to invest further in the province’s future.

I believe Nova Scotia can open itself up to the shale-gas market through safe and regulated fracking and use that introduction to become a “have†province again. What it will take is Nova Scotians using the abilities they have prided themselves on for so long: intelligence, sober thought, planning, and hard work.

Nathan holds a B.Sc in Geology from Acadia University. He was born in the Valley and raised on the Blomidon shore. He and his wife are currently raising their family in Grande Prairie, Alberta, and working in the oil and gas industry.

The risks of fracking in the Valley – a proper perspective

Richard Gagné, P.Geo.,

There is no denying the need to reduce our dependency on coal, oil, and gas. But the alternatives – hydro-electric, solar, wind, and tidal – each have their own environmental issues, and most are still years from being commercialized. Until then, we must depend on fossil fuels to make electricity, to heat our homes, and run our cars.

Our need for oil & gas will probably continue long after alternative energy is in place – in places where the alternatives cannot reach, and as the feedstock material required to make the plastics and resins we will need to build windmills, tidal turbines, and for other manufacturing.

The Ivany Report emphasizes the urgent need for Nova Scotia’s economy to move forward and in new directions. The Michelin Tire layoffs announced this week help make that message for change very loud and clear! Perhaps the economic benefits that oil & gas development can bring to Nova Scotia is one way to help accomplish that change? But that might mean having to accept the use of hydraulic fracturing in some circumstances.

Onshore oil & gas exploration is not new to Nova Scotia. The first wells in Canada were drilled in Cape Breton in the 1800s. But those were shallow wells drilled using old technology that did not produce much. Today the exploration focus is on gas, shale gas, and coal bed methane. Although no commercial discoveries onshore Nova Scotia have yet been made, the success in new Brunswick bodes well for future discoveries in Nova Scotia, since both provinces have similar geological settings.

Having explored for oil and gas years ago, and working now for more than 25 years as a hydrogeoscientist on surface water and groundwater resource development and protection, I feel I can rightly say that fracking can present risks, just as many other accepted industrial activities can pose risks to the environment.

But hydraulic fracturing, which was invented in 1947, commercialized in 1949, and used over 2.5 million times worldwide for oil & gas development, is not new. So the risks are well understood, and are generally no greater than those posed by most any other type of conventional and non-conventional oil & gas development activity.

If we are to proceed with oil & gas development in this province, we must be sure that it is done right. That means that, as well as getting jobs, Nova Scotians also must be kept informed of what the industry really is all about – both the good and the bad.

Not all oil & gas wells need fracking. Oil & gas development can be done in environmentally sound ways, but there may be spills from time to time which will need cleaning up. Sea water can be used for fracking, and fracking return and production water can be reused once the industry is up and running and proper treatment and recycling facilities are in place.

The anti-fracking advocates purposefully spreading their misinformation have done so solely with the intent to cause confusion. Their messages have set fears in people where fear may not be warranted, and have muddied matters to the point where most don’t known where the actual risks may or may not exist from having an onshore oil & gas industry in Nova Scotia.

For example, many Valley residents from Annapolis to Wolfville have been led to believe that their water supply wells will be poisoned and their property values will drop if “fracking†is allowed in Nova Scotia. Well, lets consider the following geologic facts:

Having oil & gas present requires having the right mix of rock types and burial conditions for organic materials deposited with shale to convert to oil or gas, and to be stored in the rock. The only geologic deposits onshore Nova Scotia where such conditions might exist are within the Maritimes Basin, which is characterized by a 3,000 m thick accumulation of sedimentary rocks deposited in alluvial, fluvial and lake environments (the Horton Group), overlain by a mainly marine sequence (up to 1,500 m thick) of clastics, limestone, and evaporites, including gypsum, anhydrite and salt (the Windsor Group).

The areas shaded orange in the map below show the extent of the Maritimes Basin deposits in Nova Scotia. It is clear that these deposits do not extend into the Valley and as such, there would be no interest for any company to do exploration for oil & gas in the Valley, let alone fracking. Therefore, any concerns about fracking on water supplies and property values in the Valley that the anti-fracking advocates may have been trying to advance are totally unfounded.

Richard Gagné has 35 years geoscience experience, 27 of them in the water resources sector, of which 22 are in private practice. Rick obtained a B.Sc. with Honours in geology from Carleton University, where his focus was on petroleum geology and surface water hydrology. He completed graduate level studies in groundwater at TUNS (now DalTech). Rick is a past chair of the Halifax Watershed Advisory Committee, and one of the founders of Geoscientists Nova Scotia. In his practice, Rick undertakes projects relating to industrial and municipal surface water and groundwater supplies; watershed-scale hydrologic and aquifer assessments, and water supply development, permitting, and protection.

The above comic strip was written and created by Mark Oakley

SOCIO-ECONOMIC UPS AND DOWNS TO FRACKING

by Edith Callaghan, School of Business, Acadia University,

Supporters of hydraulic fracturing in Nova Scotia predict energy independence, enhanced employment opportunities, and significant tax revenues—a veritable boon for our beleaguered province. Alternatively, critics predict ecological destruction in the wake of hydraulic fracturing coupled with a net drain on our economy and communities. How can we know which way to turn?

Luckily (or unfortunately, depending on your perspective), there are a number of communities to our south that have experimented with hydraulic fracturing. These experiments have gone on long enough for researchers to collect meaningful longer-term data that help us understand the dimensions and potentialities of the impacts of fracking on the local economy and community.

Initially, there is an economic and community welfare benefit to the introduction of fracking to a community in terms of investment, jobs, and tax revenues. However, in the longer term (within 5-10 years), the direct economic benefit is significantly reduced. Part of the problem is the rapid drop-off in shale-well productivity. Examples of shale-well productivity in North Dakota’s Bakken Formation seems to be typical, with depletion rates of up to 69% in Year One and 94% over the first five years (“Drill, Baby, Drill,†2013).

According to studies, actual job creation from fracking is less than promised by industry. In Pennsylvania, it was reported that the Marcellus Shale operations resulted in 48,000 new hires. Further study showed this not to be true. New hires is not the same thing as new jobs: when migration from one position to another and job loss in ancillary industries was taken into account, new jobs were estimated at 5,699. While this amount of job gain to a small economy is not insignificant, it is also far short of the promise from industry. Whereas the shale-gas industry estimated 31 jobs per well drilled, the actual is more like 3.7 jobs per well (Multi-State Shale Research, 2013).

The impact of this on families and communities has not turned out to be positive. In West Virginia, 12 of the 14 mining counties had an average median household income of $30,655, below the state’s median household income of $37,356, and 13 of the 14 mining counties had family poverty rates averaging 18.6%—higher than the state average of 13.2%. This study of West Virginia’s economy concludes:

West Virginia counties with a concentration in mining saw their economic performance dramatically decline after an energy development boom. Today, their economies are weaker than the rest of the state, and they are ill-positioned to compete and grow.

Some may argue that any economic growth is better than none. This might be true; however, we also must consider the other costs associated with hosting this industry. According to a CaRDI Report (#14, 2011), the costs to communities from road damage and enforcement are significant. Heavy trucks damage roads. Millions of gallons of water and additives must be trucked to and from drill sites during the life of the well. Apparently, in the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania the maximum that shale gas companies will pay for road damage covers only 10-20% of the cost of road repair. The state has also discovered that it is necessary to patrol for trucks carrying over the legal limit of 80,000 lbs per semi-trailer truck. In 2010 and 2011, 42% of the roadside inspections of shale-related trucks on the roads resulted in pulling the driver and/or the vehicle out of service. The cost of this increased inspection was $550,000.

In a separate long-term study of the relationship between oil and natural gas specialization and socioeconomic well-being in the interior U.S. West, researchers found that specialization in this sector has led to increased crime rates and decreased levels of education for communities (Headwaters Economics, ND).

The health of citizens also appears to be negatively impacted by shale gas. One study found that there was a significantly reduced average birth weight among infants born to mothers living within a 2.5 km radius of a shale well. The cost to society for a low-birth-weight baby is estimated to be $51,600 per infant (Hill, 2013). In another study, examination of shale-well reserve-pit contents found radiation in soil and water that exceeded regulatory guideline values by more than 800%(Rich & Crosby, 2013). Findings such as these have led the Pennsylvania State Nurses Association to call for a moratorium on new drilling permits for shale-gas exploration.

Finally, we need to consider impacts on other sectors of the local economy. Researchers have noted specific concerns related to impacts on tourism and agriculture. With respect to tourism, the concern remains theoretical. To my knowledge, no hard data has been collected regarding the impact on this sector: we can only hypothesize. With respect to agriculture, however, data is beginning to come in. One study examined 24 livestock farmers across six states involving multiple cases of extreme health impacts, including sudden death, reproduction problems, reduction in milk production, neurological damage, and respiratory problems. (Bramberger & Oswald, 2012).

In conclusion, I suggest that if our goal is to build a healthy, productive, and innovative economy and society, fracking is likely not going to get us there. Yes, if we go down this route, there will be short-term gains. However, the longer-term costs to our health and economic welfare will outweigh those gains. Instead, I support efforts to build a clean, alternative-fuel economy. There are many economies around the world that are doing very well in this clean-fuels sector. If we move ahead with a clear, clean vision, I believe that we will be able to join the leaders in the clean economy of the future.

References upon request.

Edith is a professor with the School of Business at Acadia University. Her scholarly interests and expertise include sustainable consumer behaviours, business sustainability and the natural environment, community sustainability and resilience, and community food and energy issues. She is chairperson for the Nova Scotia Food Policy Council and an active volunteer in the area of bringing food security to Nova Scotia.Â

WINDSOR BLOCK – NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA

Editor’s note: To help give context to this issue, the following is from Triangle Petroleum’s website. Triangle is the Denver-based company that owns the shale gas production lease in the province. To find the full article, go to: trianglepetroleum.com

The Windsor Block covers 474,625 gross acres in the Windsor Sub-Basin of the Maritimes Basin located in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada. The property is within 25 miles (40 kilometers) of the Maritimes & Northeast Pipeline which supplies gas to one of the largest markets in North America – the northeastern United States….Royalty rates in the province are a very reasonable 10% and initial production from new fields may qualify for a two-year royalty holiday.

From May 2007 to June 2008, Triangle executed the first phase of the Windsor Block exploration program consisting of a 2D and 3D seismic program, geological studies, and drilling and completing two vertical test wells (Kennetcook #1 and Kennetcook #2). From July 2008 to March 2009, Triangle executed the second phase of the Windsor Block shale gas exploration program consisting of drilling three vertical exploration wells (N-14-A, O-61-C and E-38-A) and completing one of these wells (N-14-A).

On April 16, 2009, Triangle executed a 10-year production lease on its Windsor Block…The specifics of this production lease include the following highlights:

- Triangle has rights to conventional oil and gas in the area, which includes shale gas, in both the Windsor and Horton Groups, excluding natural gas from coal. Triangle does not believe there are any prospective coals within the Windsor Block.

- To retain rights to this land block, Triangle has agreed to drill seven wells to continue to evaluate the Windsor Block prior to April 15, 2014. These wells are to be distributed across the land block to fully evaluate both conventional and shale resources. Areas of the land block not drilled or adequately evaluated after the fifth year are subject to surrender.

BENEFITING FROM NOVA SCOTIA’S ONSHORE OIL AND GAS POTENTIAL

Editor’s note: In April, 2011, the Dexter government announced that it would review hydraulic fracturing, identifying any potential issues surrounding the process and what practices should be adopted to best ensure safe, sustainable development in the province. The review was extended in April of 2012 until mid-2014. The government then announced, in August 2013, that an independent review would be conducted by Cape Breton University president David Wheeler. Although March 31, 2014, marks the end of the acceptance of public feedback, many letters have already been made public.

The following is part of the comments from The Maritimes Energy Association. For a link to the full release, go to: maritimesenergy.com

There is also the potential for significant environmental benefits from producing natural gas here in Nova Scotia. With roughly 75% of the province’s electricity generated by coal-fired plants, a supply of local natural gas provides the option of a move to a cleaner fuel source. While renewable energy projects in the future will help cut the province’s reliance on coal, natural gas provides an attractive “transition fuel†to a cleaner future with fewer quantities of nitrogen oxides and carbon dioxide than burning coal or oil. With investment in infrastructure, Nova Scotia could eventually export cheap, clean natural gas electricity to other provinces or the United States who may rely currently on coal to produce power.

The benefits of hydraulic fracturing to the economy of Nova Scotia can be significant. The industry will provide a new demand for goods and services that can be provided in the province, as well as add jobs to the economy. Such new activity generates revenue for the provincial government through taxation and through royalties in the production phase.

When reviewing regulations, it is important to weigh the benefits that come from development. That is not to say development at any costs, but good regulation provides the balance. Protection of the environment is important, so too is the maximization of local economic benefits. Regulations and guidelines can reflect the expectation that the local supply chain is engaged and informed of procurement opportunities.

Onshore oil and natural gas development can be a game changer for our province. There are significant environmental and economic benefits. A stable, robust and timely regulatory regime is essential to ensure environmental risks are mitigated and the public interest protected.

Any industrial activity has a social and environmental impact, onshore petroleum is no different. While this may be a relatively new activity for Nova Scotia, the industry has been successfully and safely developed in other jurisdictions, specifically in Western Canada. Thousands of wells have been successfully brought to production by hydraulic fracturing with few incidents. Reviews of these incidents show not a failure of the regulatory regime, but a failure to properly adhere to existing regulations and best practices.

While your scope primarily focuses on issues about water, this is an opportunity to ensure that the complete regulatory framework mitigates risk to the environment and public health and safety.

However, it is also an opportunity to ensure there is a full and fair opportunity for the local supply chain to participate and benefit throughout the exploration and production phases of this industry. While this review concentrates on environmental issues, we suggest it also review how moving forward, local benefits are maximized to take advantage of the opportunities and potential provided by the onshore energy sector.

A COMPLEX ISSUE

Jennifer J. West, M.Sc., P.Geo. Geoscience Coordinator Ecology Action CentreI am a reluctant environmental activist. Although I have given dozens of presentations against fracking around the province, written letters to the editor, spoken with the premier’s office and several government caucuses, I did not think that I would take this path. When I joined the Ecology Action Centre in 2010, I was excited to run a community-based groundwater monitoring program called Groundswell. As I worked away on this project, people would walk past my office door, stop, and turn in and ask, “Jennifer, you don’t know anything about fracking, do you?†and I admitted I didn’t. After some research, I decided I was not keen to get involved with an issue that, as far as I could tell, would threaten groundwater, surface water, air quality, community values, and energy security. I didn’t think that I could willingly step into such a complicated mess of an environmental issue and make any sense of it.

Fast-forward four years, and I am up to my neck in all things fracking, waste-water ponds, coal-bed methane, and unconventional oil and gas. I was right about it being a complex issue, but I have been surprised about how I made sense of it. It has taken me three years and countless hours of research and discussions, but I have come to understand fracking most clearly through the people I have met who are concerned about it.

I have met residents and cottagers in the Valley and on the North Shore who learn about the vast areas where fracking could take place and the truck traffic and smog that could ensue. Farmers worried that fracking could make their livestock sick and their fields sterile. Foresters afraid that fracking could affect the woodlot and forest habitat their family has worked to protect. First Nations people who feel that fracking will break mother earth—pollute the groundwater that connects all people.

Politicians of all stripes, and bureaucrats who fear fracking’s impact on their constituents’ way of life. Lawyers who see how fracking has affected property values and insurance coverage in other areas. I have met architects, dentists, carpenters, realtors, doctors, IT professionals, students, artists, seniors, and hundreds of people who care about Nova Scotia, and who have researched the impacts of fracking on their way of life.

Without having forged relationships with these people, each with important roles in our communities, I would never have been able to make sense of how this complex issue would affect Nova Scotia as a whole. They have taught me that this is a grassroots movement that comes from fear about losing our most basic rights: clean water and air.

All of these people are connected by their concern about fracking, and have formed a strong web across the province. They are writing letters, hosting movies, talking to MLAs and councillors, presenting at council meetings and helping other groups learn about fracking. They are making a difference, too: government and companies are listening. We must keep this web strong for all Nova Scotians today and in the future.

This month, I am looking back on the people I have met, and seeing them contribute their stories and concerns to the provincial review of fracking. I can only imagine that the panel of experts, each of whom also have roles in our communities and who have families and homes in Nova Scotia, will see the big picture of fracking’s impact on our Nova Scotia way of life.

To send a submission to the review panel, email Margo at hfreview@cbu.ca before March 31, and please share it with your friends and families as well.

A graduate of Dalhousie University with a Master in Earth Science, and a professional geologist, Jennifer West is the Geoscience Coordinator at the Ecology Action Centre. Jennifer grew up in the Kennebecasis River Valley in New Brunswick, and has lived in Halifax since 2002. She worked as an environmental consultant with several local firms, taught a first-year geology course at Dalhousie University, and conducted home energy audits with Clean Nova Scotia. Jennifer’s focus is on the Groundswell Project, which aims to improve groundwater management in Nova Scotia communities with existing groundwater quantity issues. In addition to such hobbies as cooking, knitting and running, Jennifer enjoys long walks on beautiful beaches with her husband and young daughter.

Â